The intermittent war

Ongoing warfare

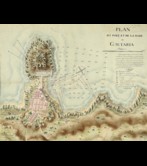

The siege of Hondarribia and the sacking of the bay of Pasaia (1638)

Ever since it was established as a villa, Hondarribia has been of key strategic importance, both as Navarra’s gateway to the sea and the first fortified frontier town. It was besieged in the 13th century and in 1521 was taken by troops who were trying to win back Navarra. The siege in 1638 occurred in the context of the 30 Years War. Despite the heroic two-month resistance that earned it the honorific title of City – with the loss of much human life and material damage – this marked the decline of Spanish power and the rise of France, ratified in 1659 in Bidasoa with the Peace of the Pyrenees. At a local level, the resistance didn’t prevent the destruction of areas in Navarra around Bidasoa, of all the mills and foundries and many houses in Irun, the burning of Errenteria, the sacking of the bay of Pasaia and a major naval defeat in Getaria.

Change of monarchy and maintaining the fueros

The death without heir of Carlos II and the naming of the French Phillip of Anjou (Felipe V) led to a war between the houses of Austria and Bourbon. This was not just a dynastic question, because it involved all of the European powers because it was central to the question of imperial control, despite Spain’s decline.

The new monarch arrived in the province in 1701 and assessed its fueros. The result of the Bourbon plan for the Basque area, unlike that of the Crown of Aragón (under which the fueros were abolished and integrated into Castilian law) did not lead to clear economic or political reform. However, a process of administrative and territorial unification and the creation of a national market were initiated. Among other measures, an important decision was the plan to move customs from the Ebro to the coast. This measure particularly affected Bizkaia and Gipuzkoa because it meant a rise in the cost of wheat and made the extensive trade in contraband more difficult. There were popular protests and in 1718 provoked the first “machinada”. It was met by fierce repression but in 1723 the old customs regime was restored. The provincial institutions, and the oligarchy that ran them, continued to grow stronger, backed by popular sentiment against Bourbon profiteering.

Berwick and the taking of San Sebastián in 1719

France opposed the new monarch and allied itself with its old enemy, England, against the Mediterranean aspirations of the Hispano-Italian Bourbons. As a result, in 1719 troops gathered in Bidasoa and took the fortified towns of Hondarribia and San Sebastián. In spite of being considered an “enlightened war”, less brutal compared to previous sieges, the region suffered the consequences.

Wars in mid-century

International affairs, with their military consequences, continued to affect the Province. Although not in the front line, forced recruitment caused a great deal of anger throughout the 18th century. Local bodies put down mutinies and collaborated with the Crown in troop deployment and the persecution of fugitives and deserters. What happened, in fact, was that they captured other people described as “undesirables” in order to fulfil their quotas and levies for the infantry in Piedmont and Savoy.

The revolution comes to Gipuzkoa

At the end of the 18th century the French Revolution arrived with all its violent consequences and, above all, established the basis for the great conflict of the 19th century: from now on the struggle was not so much territorial as ideological, between the old regime and liberalism.

In July 1794, Convention troops took control of most of the region. The Gipuzcoa authorities tried to negotiate a declaration of neutrality and collaboration for the Province with the Republic in exchange for respect for its religion and its fueros. However, not all local leaders were in agreement, and in Arrasate they set up a new Diputación which went to war with the invader. The 1795 Peace of Basel gave Gipuzkoa to the Crown in exchange for the island of Santo Domingo. Those who tried to negotiate with the Republic were viewed as traitors and blamed for the loss of the Caribbean colony. Furthermore, the entire Province was branded as a traitor and the fueros were abolished, a decision that a century later would provide the key to understanding the political and violent developments in the Basque region.

Taking stock at the end of the century

The enormous destruction caused by the war affected a densely populated region with an agricultural system already at its limits, the iron industry in a state of collapse, a decline in sea trade and therefore to shipbuilding and with the Diputación in debt through building transport infrastructure. At the same time, the legal and political framework was being thrown into question by the creation of a united and centralist Spanish market and regime. As a consequence, there was an increasing banditry, which only made things worse. The banditry had social and economic causes, although in later years it took on a political coloration.

_petita.jpg)