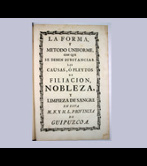

Universal nobility

The Hidalguía Universal (universal nobility, a proclamation that meant that anyone born in Bizcaia was of noble birth, however lowly they were), which was associated with a solar conocido (known ancestral home) formed a key part of Gipuzcoan society under the Old Regime. Fundamentally, it declared anyone from a caserío or ancestral domain to be of noble birth and therefore all their descendants were, according the phrase coined at the time, “free of any evil blood such as Jewish, Muslim or any other sect condemned by the Holy Office of the Inquisition”.

This proclamation was one factor that in the medium term led to the success of the villas system in the Province. Although it was only a theoretical idea, it was made real in a series of privileges the Province obtained from the kings from the 14th century onwards, in general for military service provided by the villas.

Its later consolidation into the law led to a proliferation of tests of hidalguía as essential documentary proof in order to obtain certain types of work. It should be borne in mind that the hidalguía is as Borja Aguinagalde said, “above all, the document that allows you to become a resident in a villa if you’ve come from somewhere else, both within Gipuzkoa, moving from one area to another, as well as those with the right to leave the region or the right of others to come from other parts or kingdoms. For social reasons of another kind, within the sphere of defending the honour and nobility of the territory, from the 16th century the hidalguía was the system adopted to control, on the one hand, the movement of people within Gipuzkoa, and on the other, to control access to positions of power which were not open to those who could not prove their hidalguía”.

Bearing in mind that nobility carried with it exemption from paying certain taxes, from performing military service (though not naval service, which was organized in the Gipuzcoan ports) and ancient privileges, any person from Gipuzkoa in Castille was extremely interested in acquiring their hidalguía. Between 1608 and 1610, the Province of Gipuzkoa won the explicit recognition of the Crown for the hidalguía to be applied across the entire territory based on the idea of a dominion that extended from time immemorial. This argument was revived in the redrafting of the fueros (charters) in 1697, in Chapter 2 of Section 1 that stated that since the Flood no one else had been Gipuzcoan except for those born and originating within its territory, who were lords of themselves and of pure race. The people of Gipuzkoa were, therefore, de facto noble in origin, always had been and had never mixed with anyone else. This nobility is not conceded by anyone but exists of itself.

By calling themselves nobles, the people of Gipuzkoa established the basis for justifying their right to organize their own affairs, something that was already a reality. It was, therefore, a process that ran parallel to the creation of political institutions. These institutions were being created by subjects who were all equal and who invested this authority and legitimacy in themselves. They refused to recognize that the descendents of the Parientes Mayores could lay claim to any political superiority. At the same, time anyone who couldn’t demonstrate their hidalguía was excluded from this political structure.

The proof of hidalguía was also a useful mechanism to keep out external competition and maintain control over political organizations. In the villas it served to distinguish between residents and mere “inhabitants”. The residents could expect certain social, economic and cultural standards, and were allowed to occupy government posts as well as having rights and duties. The inhabitants, on the other hand, were excluded from the local and provincial social political bodies.